My name is Craig Brown, and I have more firsthand experience with job loss than most people could imagine.

The last major recession in the United States hit in 2008, resulting in a wave of layoffs that took many by surprise. Countless workers believed government assistance would be there for them, only to find they were, essentially, on their own. While they could receive a modest unemployment check and continue their health insurance through COBRA, the cost was prohibitive (my own COBRA payment was nearly $2,000 per month!).

Many people made financial and life decisions based on the assumption of a stable income, without planning for the possibility of a layoff.

Why do layoffs happen? Primarily, because there’s no real accountability for corporate decision-makers. Executives can make poor choices as long as the company tolerates them, with no repercussions beyond the corporate walls.

For instance, a company may go on a hiring spree during busy times, promising long-term employment, only to lay off those workers later without consequence. Layoffs also help companies avoid discrimination claims, as they can cut a diverse range of employees rather than targeting specific groups. Unlike in some other Western countries, where layoffs come with serious implications, the U.S. lacks similar protections.

In 2008, layoffs were a foreign concept for many Americans. Workers who had been with the same company for 20 years or more, with plans to retire there, were blindsided by sudden terminations. The psychological toll of a layoff can be severe. Few are prepared for the aftermath, including the loss of workplace friendships. In the U.S., where most people get limited vacation time, coworkers often become our main social circle. We share meals, stories, and daily experiences with them, even calling them “friends.” However, after a layoff, laid-off workers quickly discover that those “friends” often don’t stay in touch. It’s a harsh reminder that many of these connections are more professional than personal. In American culture, people tend to focus on themselves and their immediate family, making post-layoff isolation a common and painful experience.

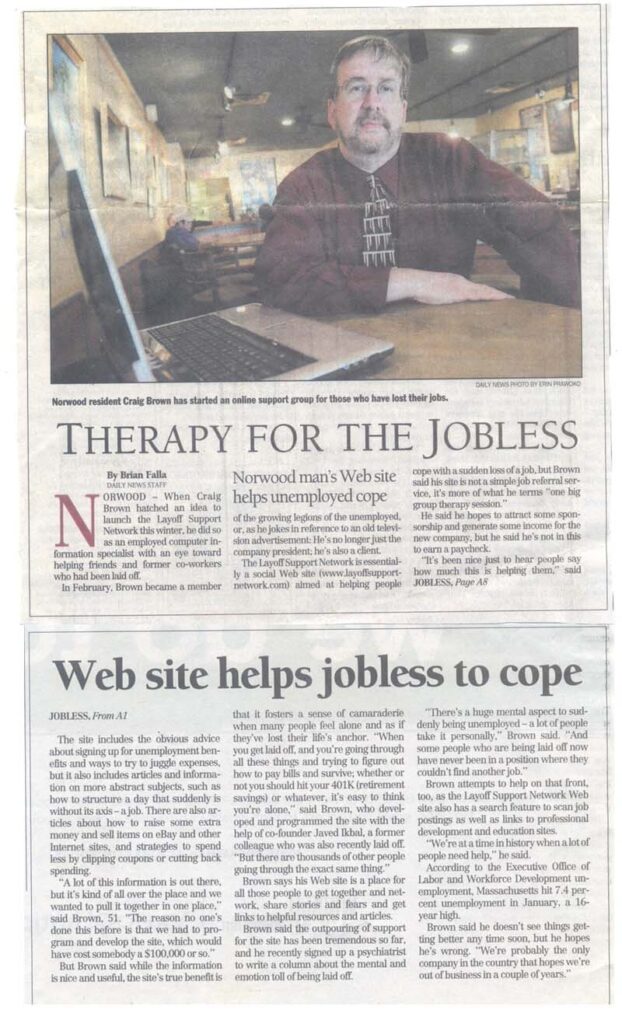

In 2008, I wasn’t laid off—but many of my ex’s friends were. They reached out to former coworkers for support and empathy, only to find a cold shoulder. Instead, they turned to me. Realizing I might be able to help, I created the Layoff Support Network, a community that eventually grew to become the largest privately funded relief organization of its kind in the United States.

I was in a unique position to understand job loss. Over the years, I’ve probably lost my job more times than anyone you know—not due to poor performance, but because of the nature of the work that captured my interest. I entered the tech industry around 1980 as a software engineer, back when layoffs were virtually unheard of. Back then, if a project failed or a new technology direction didn’t pan out, companies would cancel the project but allow employees time to find another role within the company. Honesty and transparency were the norms.

Over time, however, that began to change. Companies chasing emerging technologies faced increased risk—and were often wrong in their predictions. When a project got canceled, the job itself would vanish, leaving employees scrambling for an internal position or facing layoff. I sought out roles on the cutting edge of technology, and that choice meant a higher degree of uncertainty and risk. Many of my projects were canceled, resulting in a cycle of job loss and transition that became familiar.

After years in development, my passion for creating new technologies naturally led me into the field of Information Security. This field emerged as the Internet became a part of daily life, with people suddenly entrusting their personal information to online platforms. I didn’t set out to work in Information Security, but my path led me there.

At that time, corporate accountability was minimal. When mistakes were made in American companies, the corporate veil protected individuals at the top from facing real consequences. However, customer backlash was still a factor, and often the blame fell on Information Security teams. If a manager made a misstep that jeopardized data security, the response was simple: “Fire the information security manager.” This was before regulatory measures required such actions—it was just a convenient way to quiet the fallout. As a result, being an Information Security manager was even more precarious than being a software developer in the 80s and 90s.

Eventually, as layoffs became more widespread across industries, I found myself caught up in a few of them, too. The field of Information Security had grown in importance, but that didn’t make it any less volatile.

At first glance, being an expert on surviving unemployment might paint me as the biggest loser on earth. Well, you might be right in that assumption. But the fact is, I have 35,000 thank you letters from people that disagree.

The value of understanding financial survival—especially in times of job loss—became even more apparent when I co-authored The Laid-off Ninja with the other founder of the Layoff Support Network. The book was a deeply personal project, born from years of firsthand experience and the collective wisdom of our community. It didn’t take long for it to become a best-seller in its category on Amazon, proving that navigating the world of layoffs and financial resilience is a skill people need, now more than ever.

Note that any profit from the book was used in free seminars, during which we also gave away copies of the book. The book was followed by a monthly publication called Layoff Life.